MetroHealth Rehabilitation Institute clinicians and researchers recently celebrated a research success: the first demonstration of high-frequency electrical nerve block (ENB) of muscle contractions in humans.

The success of this intraoperative experiment is the springboard for a full clinical study of patients with spasticity, and efforts are now underway to secure funding, technology and FDA approval to launch the study.

The research—led by Jayme Knutson, PhD, Director of Research, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R); Kevin Kilgore, MD, PhD, Staff Scientist in the Departments of Orthopedics and PM&R; and Niloy Bhadra, MD, PhD, Staff Scientist, Department of PM&R—aims to use high frequency alternating electrical currents to provide instant and adjustable spasticity relief in patients who have experienced a stroke, traumatic brain injury or spinal cord injury.

Spasticity is a serious condition that we see in many of the patients treated here,” says Dr. Knutson. “Muscles contract involuntarily and prevent normal movement, making daily tasks like eating and dressing all the more difficult. Plus, spasticity can be very painful and if left untreated can cause joint deformities.”

Because current treatments for spasticity such as oral medications and injections don’t always work well and may have side effects, MetroHealth researchers have continued to seek a better option.

This research is a milestone accomplishment after two decades of research conducted by Drs. Kilgore and Bhadra, who developed the ENB techniques in animal studies.

“As an institution, we’ve been inching toward using ENB technology in humans,” says Dr. Knutson. “Now we’re on the cusp of clinical studies that, if successful, could revolutionize the treatment of spasticity.”

Potential for Patient Control of Spasticity

The researchers at MetroHealth envision a medical device that could give patients with spasticity on-demand control of their muscle tightness, like a dimmer-switch. Therefore, Dr. Knutson’s team wanted to test if this new electrical nerve block method would work to turn off involuntary muscle contractions that appear after neurologic injury to the brain or spinal cord.

This research really has the potential to change how spasticity affects people who experience it—this is a potential game-changer for patients,” says Juliet “Jacy” Zakel, MD, Director of Spasticity Management at the MetroHealth Rehabilitation Institute.

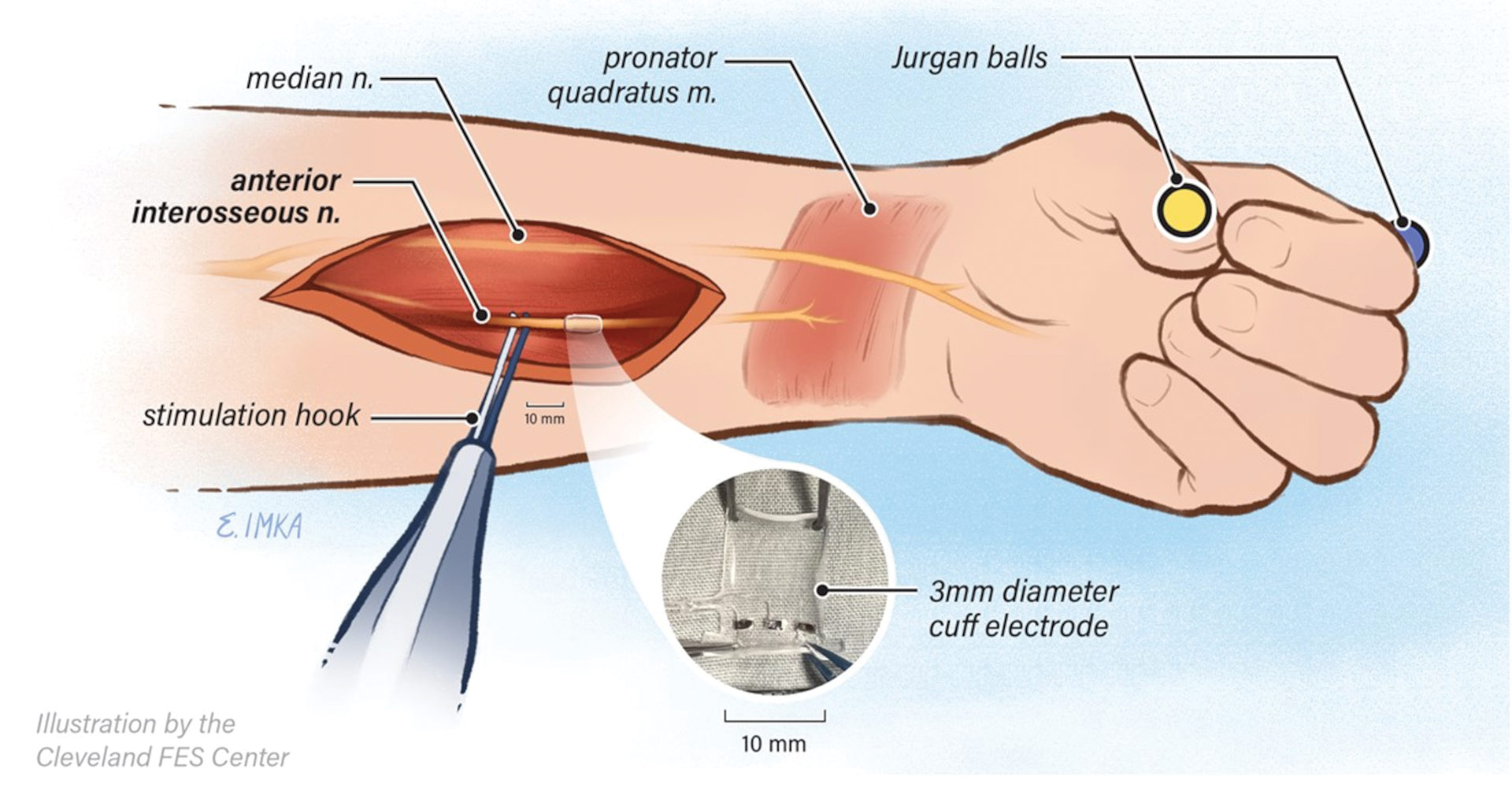

The team tested the ENB in an individual having a surgery involving the muscles and nerves in the arm and hand. During the surgery, a blocking electrode was placed around the anterior interosseous nerve which innervates the pronator quadratus (a nerve going to a wrist muscle). An electrode probe positioned near the nerve proximally (“upstream”) from the blocking electrode was used as the stimulating electrode. The stimulating electrode was turned on, delivering a small electrical current to the nerve that caused the muscle to contract. While the stimulating electrode was still on, the blocking electrode was turned on to deliver the high frequency ENB current that was expected to block the nerve and cause the muscle to stop contracting.

“The stimulating electrode caused the muscle to twitch. Then we turned on the nerve blocking electrode and the twitching stopped,” Dr. Knutson recalls. “We then turned off the nerve blocking electrode and the twitching returned—and the whole OR cheered! It was the result we were hoping to see.”

This was repeated several times with different adjustments to the blocking electrode settings, which allowed the team to see that different settings produced different degrees of blocking effect: dimmer-switch control! This finding, along with the demonstration of immediate reversibility, are some of the most exciting as it suggests that future users may be able to partially reduce spastic muscle contractions in a way that may increase function.

With the success of this first intraoperative demonstration, the researchers will continue additional intraoperative experiments on different nerves while simultaneously pursuing funding and FDA approval to launch a phase I clinical study.

“If our new method of nerve block works, people with muscle spasms or muscle tightness will be able to turn the nerve block on and off when they want,” says Dr. Knutson, “so they can control when, how much and for how long they get relief from muscle tightness.”

Additional members of the study team include Kyle Chepla, MD, Surgeon, Department of Plastic Surgery; Richard Wilson, MD, Interim Chair, Department of PM&R; Michael Fu, PhD, Staff Scientist, Department of PM&R; Emily Imka, BFA; and Shane Bender, MS.